Sports pages, protest and profit with Howard Bryant

Not so long ago, the sports page stood apart from the rest of the newspaper, but sports journalist Howard Bryant has observed and documented a change in his decades on the job.

“When I was in grade school, the sports page was the place you went to be left alone, to get away from whatever was on the editorial page,” he shared. “It’s important to understand now that sports is a multibillion-dollar machine.”

In his Feb. 16 appearance with the Lenoir-Rhyne Visiting Writers Series in P.E. Monroe Auditorium, Bryant reflected further on how the changes in the business of sports and media reflect and shape culture during a Q&A with Rebecca Alt, Ph.D., assistant professor of communication.

“The reason you got into journalism was that you were the conduit to the public, in the business of asking questions to represent you,” said Bryant. “The idea and ability of journalism — it’s so different now. Our business has a lot to do with it.”

In his introductory comments about Bryant, communication studies major Nolan Metcalf ’24 alluded to the way Bryant’s body of work bends the old and the new rules of journalism, blending sports writing, political insight, historical context and social commentary.

“Writing is a universal way of healing and processing emotions, and often it can be our last line of defense when actions fail us. It is a special moment in history when someone comes along and makes their mark by sharing their words in a sequence that can inspire others or simply change their perspective,” said Metcalf.

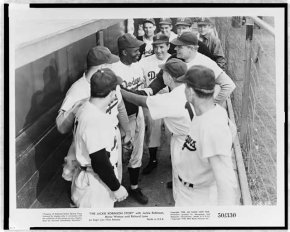

Bryant’s facility for blending the divisions between sports, politics and culture in his writing emerged in a discussion of his 2018 book “The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America and the Politics of Patriotism.” Sports have never truly been apolitical in America, which holds doubly true for Black athletes, whom Bryant described as the most important black employees the country has ever produced.

“In order for Black people to play sports, you had to have a political movement, and the reason it required a political movement is because we have always treated sports in this country as the antidote to racism. We believe in meritocracy.”

That meritocracy integrated sports teams before any other American institution, starting with baseball in 1947, one year before the U.S. military and seven years before public schools. At the same time, protest and activism present a challenge for teams’ and leagues’ profit margins — a defining conflict for sports and sports journalism then and now.

“What’s really interesting about this whole idea of Black athletes being activists — they’ve always been activists. Always. The reason is their celebrity, their notoriety, influence and visibility,” Byrant responded to a question about recent examples of Black athletes engaging in political commentary and protest. “It’s only ever ‘stick to sports’ when it’s a message that an audience, or a certain audience member, disagrees with.”

Lenoir-Rhyne University students showcased their academic excellence and research expertise at the 2025 North Carolina Academy of Science (NCAS) annual meeting in late March.

View More

Lenoir-Rhyne University has selected Summer McGee, Ph.D, as the institution’s 13th president. Her appointment was enthusiastically approved by the Lenoir-Rhyne Board of Trustees after a national search.

View More