Adventures in nursing practice

After more than three decades of experience in healthcare — in settings ranging from army hospitals to prison infirmaries — Ramesh Upadhyaya DNP ’23 had seen it all. Then, as a graduate student in nursing at Lenoir-Rhyne, he discovered a whole new adventure by completing part of his clinical practice in Guatemala.

Setting his sights on medical school when he graduated high school, Upadhyaya started his healthcare career in the U.S. Army as a combat medic.

“My perception of doctors was colored by growing up watching MASH on television, until I found the doctors really weren’t like Hawkeye Pierce. The nurses, on the other hand, were so admirable, something to aspire to — so that became my trajectory,” he said.

The road to LR

That trajectory earned him a Bachelor of Science in Nursing at UNC-Greensboro, where he also completed the combined Master of Science in Nursing and MBA program.

“I applied for a teaching assistant position and took to teaching like a fish to water, so I taught in the nursing school at UNCG for about six years.”

After that, he spent a few years with the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services as a surveyor, monitoring healthcare providers for compliance with state and federal regulations.

“I’d walk into a facility, give my card to the receptionist, and everyone would start whispering. The people were really nice, but they also couldn’t wait for you to leave,” said Upadhyaya.

Moving on to the Department of Public Safety, Upadhyaya progressed from quality improvement specialist for the state’s prison healthcare system to nurse recruitment. Then the COVID pandemic changed his trajectory again.

“The recruiting events dried up with COVID, but the department really needed help in the prisons. So, I put on my scrubs and went to help. I realized what I had been missing all this time doing administrative work,” he said.

Returning to clinical practice reminded Upadhyaya how much he enjoyed connecting with patients.

“As a correctional nurse, I got to see medicine practiced in a very different way from how it’s done outside the system. Every inmate has access to healthcare as a protected right. The doctors and nurse practitioners see all the inmates on a regular basis and follow them closely.”

Upadhyaya decided to continue his education to become a nurse practitioner. He chose Lenoir-Rhyne because he saw a shared value for personal connection in the nursing faculty. “The chair of the program reached out to me and talked with me for over an hour. It showed me how deeply this program is invested in its students,” he said.

On to Guatemala

Shortly after enrolling at LR, Upadhyaya met Taylor Ramsey DNP ’21, who volunteered with All In Guatemala and now serves on its board of directors. “Out of the blue one day, she asked if I knew anyone who wanted to go on a medical mission,” said Upadhyaya.

All In Guatemala partners with the Guatemalan organization Salud y Paz, which means “health and peace,” to provide medical attention, infrastructure assistance, education and commercial development for Indigenous communities in the remote Guatemalan highlands.

Upadhyaya again connected with Kerry Thompson, Ph.D., chair of the School of Nursing, who approved his field hours in Guatemala toward clinical practice requirements and introduced him to Brittany Marinelli, director for international education.

“The Robert and William Shuford Scholarship for Studying Abroad awarded me $1000, which covered half my expenses for the trip in June 2022,” said Upadhyaya.

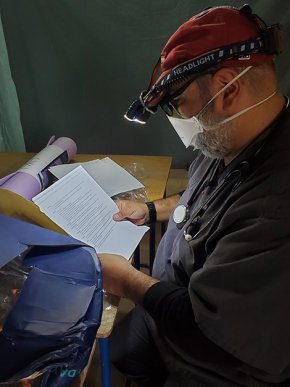

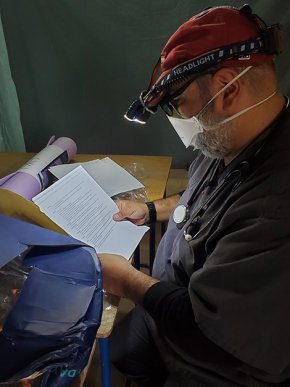

He accompanied a second mission in March 2023 with two other nursing students he brought on board: Tiesha Ward DNP '23 and Kathleen Marco DNP '25. While there, he and Marco began work with Salud y Paz to lay the foundation of a project addressing the needs of newly diagnosed diabetics among the Q'iche tribe in the remote highlands.

These missions comprise teams of students, current and retired healthcare providers, other assistants and a translator.

“I got fluent in Spanish working in restaurants in Chicago when I was younger — I learned all the bad words first,” Upadhyaya laughed. “But the Indigenous people in Guatemala don’t speak Spanish. They speak dialects of ancient Mayan, and it couldn’t be more different.”

Geography and expense keep the Indigenous population from consistent medical care. Instead, they rely on providers through a variety of organizations, each one serving a tiny percentage of the total population of Indigenous peoples.

“We saw around 500 patients in a week and treated them, and that’s pretty amazing. Since they don’t have any access to healthcare otherwise, even that little bit is better than nothing at all,” Upadhyaya explained.

He also saw similarities between the service he was providing in Guatemala and in his job in the U.S.

“You’re seeing patients who haven’t had much access to healthcare and can make a profound impact on their quality of life, even from a short encounter. That’s why I went into nursing.”

In this update, Rev. Dr. Chad Rimmer, rector and dean of Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary (LTSS), shares exciting developments as LTSS settles into its new home on the campus of Lenoir-Rhyne University.

View More

From the sports sidelines to the admission office, Zaniya Parks ’25 shows in her journey, the LR spirit isn’t just about game day—it’s about giving back.

View More