A Future Defined by Hope

Personal security remains a concern for these refugee students. To ensure their safety, names and other identifying features have been kept private.

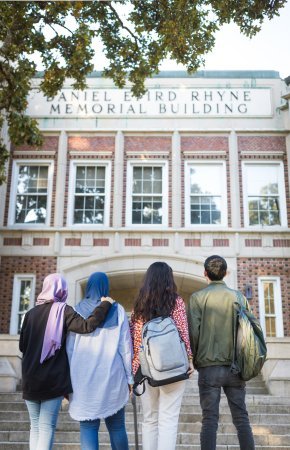

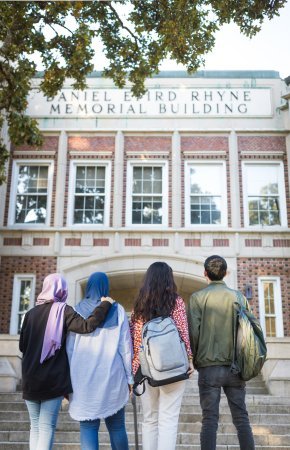

Nothing in the students’ appearance reveals the long and challenging journey they began two years ago — the one that has brought them from Afghanistan to Hickory, North Carolina. The five of them carry backpacks and wear jeans, T-shirts, leggings, sneakers and reserved smiles as they walk through the door of the International House. They hug and clasp hands with unexpected friends who have arrived through different resettlement agencies.

Eric Brandon, director of international and special projects at LR, offers a warm greeting and welcome before moving into the business of college — paperwork, dorm room assignments, student IDs. Brandon has played a key role in helping students navigate the logistics of their journey and will continue as a mentor and advisor for as long as they are on campus.

“Our first group of six students arrived in January 2023, and I see at least one of them at least once a day. We had two more groups arrive in August 2023,” shared Brandon. “They have settled well into the campus and community, are working in jobs and internships, doing well in their academics, but it takes time. I’m here to help with whatever they need.”

August 2021

When United States military forces withdrew from Afghanistan in August 2021, the government collapsed, and the Taliban forces ousted 20 years prior took control of the country. Citizens seen as collaborating with the American presence faced immediate danger, sparking a massive and chaotic evacuation.

Among those under threat were students and alumni of the American University of Afghanistan (AUAF), an independent institution established in 2006, developed with U.S. funding on the U.S. model of higher education. For 15 years, students enrolled, seeking a prestigious education and a promising future that was suddenly plunged into uncertainty.

“In Afghanistan, the American University was highly respected, at least for the people who were more liberal,” explained one of the male students in the first LR cohort. “Among people with more restricted ideologies, there were also a lot of baseless rumors about what we were taught there. In reality, AUAF was a place without bias. Inside our university, everyone was equal.”

That dedication to equality, especially equality for women, made the AUAF campus in Kabul a target. The university closed for seven months after a bombing and siege in August 2016 killed 15 and injured more than 50 students and AUAF personnel. Five years later, the campus was one of the first locations seized by the returning regime that called AUAF students and alumni “wolves trained to corrupt Muslims’ minds” on social media.

“I saw what was happening and knew what would happen to the Afghan women — and the men who were helping them — as the Taliban assumed control. I asked myself what I could do about it,” said Leah Beth Hubbard, assistant vice president for mission, engagement and innovation. “Then I thought, we have an institution, what if we could bring some of the refugees here?”

Hubbard brought the idea to university president, Fred Whitt, Ed.D., and the board of trustees, all of whom embraced the idea right away.

“These students had their educations and futures dramatically impacted by the crisis in their country and being given the opportunity to offer a helping hand, we had to extend it,” said Fred Whitt, Ed.D., university president. “Our community benefits as much from their presence and their perspectives as they benefit from the support offered here in Hickory.”

However, administrative approval was only the first hurdle. Throughout the fall of 2021, hundreds of AUAF students were evacuated to campuses in Iraq, Kyrgyzstan and Qatar, and LR was one of several universities in the United States navigating the logistics of opening their doors to the refugees.

“It was much more complicated than just putting out a call saying we have space at LR,” said Hubbard. She consulted with Mindy Makant, Th.D., associate professor of religious studies, who connected Hubbard with an immigration lawyer working with Afghan refugees, and Brandon, whose decades of experience with international students became indispensable.

From there, the team at LR collaborated with multiple organizations, including the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, the Institute of International Education (IIE), the Qatar Scholarship for Afghans Project and the Afghan Future Fund. Even with ample assistance, it took more than a year for the first five-student cohort to receive their visas to travel to the United States.

“So many American universities have stepped forward to help Afghan students, and I’m proud that we were among the first,” said Hubbard. “This is the heart of Lenoir-Rhyne, to educate individuals and to help those who need help.”

The Long Road to LR

Many AUAF students were able to leave Afghanistan during the initial evacuation in August 2021. AUAF alumni were not part of the official evacuation efforts but were offered seats on departing flights if they were available. Many — including the six who made it to Lenoir-Rhyne in the first cohort — spent weeks or months awaiting transport, ready to leave at a moment’s notice.

One of the women in the first cohort described her journey. “In October, I received an email saying there was a spot on the plane heading to Iraq. I was instructed to go to a hotel in the city to collect my gate pass. With the Taliban regime, I wasn’t supposed to go out alone, but my father and brothers weren’t home, so I took a taxi alone. At the hotel, I encountered Taliban soldiers and talked to them. They finally let me go inside to get my gate pass, but it was very scary.”

Her flight left the next day, giving her a few hours to say goodbye to loved ones. “My sister did not have the same chance. In August, she received a phone call to leave and had an hour to pack a bag and say goodbye,” she said.

While they waited, a critical concern was avoiding Taliban soldiers who might target them for their affiliation with AUAF. One of the men in the cohort had learned this lesson a few years before, when he and four friends from the university took a wrong turn on a vacation trip and stumbled into Taliban-controlled territory, where they were captured and interrogated for several days before they were released. Although he feared for his life and the lives of his friends, he tried talking to his captors.

“I was curious to know their minds,” he said. “They thought I was a spy, so they didn’t have any kindness for me. They were guided by ideologies that were sent to them through messages or videos, but it was not related to what Islam is truly about.”

The same student had been present at AUAF when Taliban forces attacked the campus in 2016 and was nearby when a later attack targeted a government building near his workplace.

“These things were part of the community, part of life when we were living in Afghanistan. It was expected to witness such events,” he said.

When they were able to travel, members of the first LR cohort evacuated with several hundred other AUAF students, first to Qatar and then on to the American University of Iraq Sulaimani (AUIS), where they were able to continue their studies. While the cohort described their experience in Sulaimani, located in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, as positive and pleasant, they knew it would not be a permanent location for them to build new lives. With visas approved, they embarked for their new home.

Welcome to North Carolina

Even a voluntary move to another country brings challenges in lifestyle adjustments. An involuntary move to another country, leaving loved ones behind, without knowing when or if a reunion is possible, increases those challenges by an order of magnitude.

“They are here until they graduate, two or three years for most of them,” Brandon explained. “Within the year they’ll have permanent residency in the U.S. I won’t say it will never happen, but some big changes would have to happen with the Taliban to make it safe for them to go home.”

Early in the process, Brandon and Hubbard worked closely with university pastor the Rev. Todd Cutter ’96, M.A. ’00, M.Div. ’04, and the Rev. Dr. Christy Lohr Sapp, pastor of St. Andrew’s Lutheran Church across the street from the Hickory campus, to prepare for the arrival of students from Afghanistan. Once the cohort was assembled, the Carolina Refugee Resettlement Agency and the Catholic Charities Diocese of Charlotte assisted with the details of resettlement.

“Our Lutheran faith calls us to do this because it’s grounded in grace and acceptance,” said Hubbard. “It doesn’t matter what faith you have, it’s about the kindness that you show others.”

Supported by the resettlement agencies and the team at Lenoir-Rhyne, cohort students settled into university housing with access to kitchens to accommodate their dietary needs. They explored and came to love the western North Carolina landscape. They excelled in their academics and found jobs and internships.

“The university provided what we needed, and the kindness from the professors and staff melts your insides because we received this kind of attention from our families, but now we are receiving it from people we hardly know,” said one of the men in the cohort.

Although several members of the cohort have family in the United States, none of those relatives are local, and some live as far away as the West Coast. The cohort members have begun to find support in the community and connections with other refugee families.

As is the case for one of the women in the group who has become close with a couple she met at St. Andrew’s. “They are older and very kind. They’ve traveled to Afghanistan and have helped many Afghan students,” she explained after returning from a short vacation with her found American family. “It was my first time seeing the ocean, so it’s hard to describe it. The world is very wide.”

The students have faced challenges since their arrival, too. For example, they rely on friends and visitors to bring them meat prepared in accordance with Islamic law from larger cities because Hickory doesn’t have a halal butcher. Sometimes they face prejudice in looks or remarks from strangers out in public. Even on the campus where they feel comfortable and safe, one of the students recalled occasionally feeling on the spot in a class as the sole representative of roughly two billion Muslims worldwide.

“It is good to have the opportunity to educate others about my faith, my background and how everything is not what they see in the media,” she explained. “At the same time, it is hard to feel like an outsider in those situations.”

Her response to this early discomfort was to get involved in campus life as a representative to other North Carolina campuses helping smooth the transition for other international students and refugees. After she graduates, the student plans to take her degree in project management and business analytics into the nonprofit sector to benefit people who have been through experiences similar to hers.

She added, “If institutions want international students to feel comfortable and their own students to have a better understanding of the world, they must show them more of the world outside this country. I want to help make those changes, not just at LR but around the state and around the world.”

These students had their educations and futures dramatically impacted by the crisis in their country and being given the opportunity to offer a helping hand, we had to extend it.

The Journey Ahead

A draw to public service and civic action is a common thread for every member of the student cohort.

One of the women in the group will complete her Master of Business Administration in 2024. She majored in marketing as an undergraduate at AUAF and interned as a scholarship coordinator with the Yalda Hakim Foundation during her year in Iraq, helping other Afghan women pursue higher education.

“I’ve had to adjust my plans and goals, but when I graduate I’d like to continue helping people, perhaps work with an organization like International Rescue Committee,” she said. “I attended a conference in Washington, D.C., last semester and appeared on a panel with other Afghan students. I made some good connections there, but I’ll see what happens when I get into the real job market.”

One of the men in the cohort had nearly completed his law degree at AUAF. He is now majoring in politics and law with plans to attend law school after he graduates in 2024. He interned with a local law firm over the summer, which led the firm to hire him as a legal assistant.

“I like political science, but I see law as more concrete and realistic,” he said. “In the long term, I would like to work with international criminal law, which is an important topic around our country. Mostly, I’m looking forward to just being able to finally practice law.”

Another political science and law major in the cohort began a long record of public service around the time he entered AUAF, first volunteering with Solace for the Children, which helped children injured during the war in Afghanistan travel abroad for treatment. He then spent some time working in the Directorate of Local Governments before helping a colleague establish a new nonprofit in Kabul.

“We converted an old bus into a mobile library. It became quite famous inside and outside Afghanistan,” he said. They called the organization Charmaghz, a Farsi word that refers to the resemblance between a walnut and a brain. He moved on to work for a think tank dedicated to collecting data related to the Afghan peace process.

“After graduation, I could go to graduate school, but I have spoken with recruiters for the Marine Corps,” he said. “I have knowledge from Afghanistan and the countries around Afghanistan, and I speak Persian, Urdu and English. I could be a good fit for work in politics or intelligence.”

In the meantime, he and his cohort continue to settle into their new lives and make plans for a future that may be uncertain but is defined by hope.

“It is nice to be able to be calm and just breathe,” he said. “Living anywhere you have peace is enjoyable.”